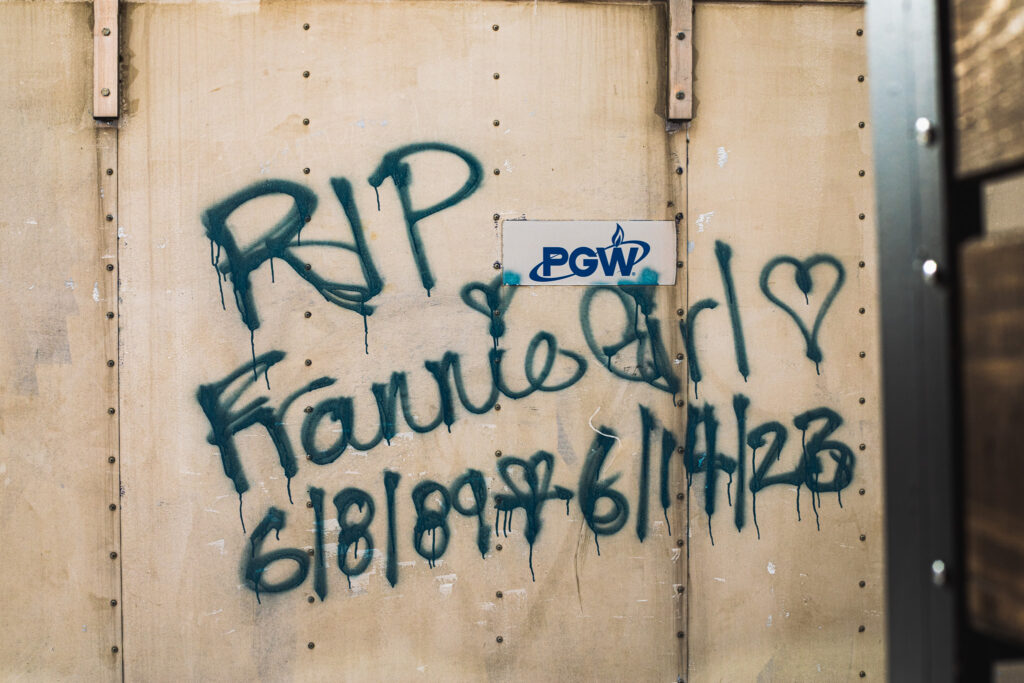

You can find a couple of reminiscences repeated in memorials around this part of the city–for “Cheo” and “Mickey” (see the map). But this is the first time I have encountered repetitions of the same memorial at multiple sites. As I walked around the streets of Kensington this summer I came across four different walls with words of remembrance for “Frannie Girl” spray-painted on them. They appeared at different times and with different colors of paint, but they seem to be written by the same hand. Not only have they been repeated, but as some of them have been distressed and damaged by the elements, it is clear that the original writer has come back a few times to touch them up.

As it happens, repetition in the context of collective memory is something I have written about before. In the wake of September 11, for example, the flag was a frequently-repeated publicly-displayed, personally appropriated symbol that appeared everywhere. It was so frequently reproduced and displayed in so many different contexts, and in so many different ways, that stores and suppliers ran out of nearly everything bearing this national symbol. News papers even printed full-page, full-color flags so their readers could put them up. The flag, which was usually found in front of government and military buildings, on uniforms, was typically a symbol displayed elsewhere on important National holidays. But after September 11, it suddenly could be seen everywhere and on everything. Similarly, I wrote about the frequent repetition of the phrase, “I wanted to do something” in news coverage of the way Americans responded to the distressing events they witnessed on television news coverage of the terror attacks of September 11 and their aftermath (if you are interested you can out the article for free here).

In this post, I want to think about the repeated reminiscences of Frankie Girl as refrains of mourning, I will explain what I mean by “refrains,” what I mean by “mourning,” and why I think this matters for helping us think about collective memory in Kensington–and elsewhere.

What is a “refrain”?

I want to begin answering this question with music, rather than philosophy. In music a refrain is a repeated phrase or line. For example, check out “Only Memories Remain” from the band, My Morning Jacket. The refrain repeats throughout the song. As the song wanders lyrically and musically, it keeps returning to this phrase, “only memories remain.” Often in music, a refrain may undergo subtle changes in meaning with each repetition, as the verses and music explore different potentials of the phrase.

With that in mind, consider the example philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari use to talk about the refrain in their book, A Thousand Plateaus. They ask that we imagine (or remember) ourselves as a child walking alone in the dark. Maybe you are (or were) walking someplace unfamiliar. Maybe you start talking out loud to yourself, or singing, or whistling to yourself as you walk. You do this, Deleuze and Guattari write, to create a mobile safety zone, a territory that keeps the forces of death and chaos at bay. You can take it with you and make it as you go, a mobile “place” you can belong as you move through spaces that feel like they are threatening. Your whistling is nervous, true, but it affords a small bit of comfort and safety, even though just like a bubble, that territory is fragile and could be burst in an instant.

I think of this when I watch the many people who use earbuds to move through the city. Whether they are listening to music or talking on the phone (sometimes quite loudly, about very personal things), they are creating a sonic reefrain that enables them to move through their urban lives. But there there are other types of such territories created by refrains. In addition to the mobile ones, there is a more stable, locatable kind of territorial refrain. Here, music and sound function just as well, as when you clean your house while listening to music or news or a podcast. Some people leave a television on any time they are in the house. Again, these are examples of creating a more stabilizing, more stable sort of territory, one of belonging. Like the person who blasts country music from his row house on York St., we use sound and other repeated elements to shore up our places of belonging against the chaos outside.

Finally, in addition to the mobile assemblages we make to move and the domestic assemblages we create as our places, refrains can work to create collective forms of stabilization, there are also collective refrains. These refrains allow us to open those other territories to one another and reach out to establish assemblages together. I can think of no better, no more Philly an example than block parties. For those who are unfamiliar, it is quite common in Philadelphia for a group of neighbors or a local business or church to pick a Saturday to close off the street and have a big party. These usually include cooking out on the street, bouncy castles and water slides for the kids, face painting, and other fun activities. But they always involve music. The PA blasts the sound which can be heard from neighboring streets. Again, music plays an important role. It isn’t just something extra, it is, like the cones and barricades that block the street, a critical component in the organizing of this collective space. Music, calls neighbors to connect, out here in the public space of the streets and create a shared, occupied place.

What is mourning?

“Mourning” is often used interchangeably with “grieving.” They are related, but they describe different aspects of the emotional and social impact of death and loss. Grieving refers to the internal, affective experience that death and loss elicits in us. In my personal experience with such losses, it feels like I have been broken or cut open and had something important torn out of me. I think very few people experience those feelings of grief who do not also communicate it. In part because the emotions are so strong they can’t just be repressed–they have to be expressed.

Grieving and mourning then are linked, two sides of a coin: one is a powerful emotional response to the irrevocable loss of someone we love and care for deeply, and mourning has to do with how we express or communicate that loss. Culture guides both sides of this coin–both how we experience and how we express the magnitude of that loss socially. Most of us (in the US at least) have some sort of memorial service, engage in a collective religious observance, maybe have a wake or “viewing” so the larger community can say goodbye and share in our loss. We generally inter our love ones in a cemetery or graveyard where we can go visit on special occasions, or perhaps we have them cremated and keep them closer to our everyday lives. I have several prayer cards, too, which I display at home as a way to remember both the dead and the living who remain.

There are other practices related to mourning which people might take. Many parks or public places open the possibility of making a donation in the name of a loved one in order to have a park bench, or even just an engraved paving stone placed in their honor. Some families ask for donations to a charity. When my dear friend and co-worker Maria passed tragically and suddenly, many of us worked with the family and students at Villanova to endow a scholarship in her name. In other places, people may dress only in black or have meals at the graveside each year or engage in other practices to both signal their grieving or additionally address their loss. However we do it, over time, the mourning process allows us to incorporate that loss into our everyday lives. We eventually learn to live with that loss.

Mourning, Memorializing, and the Refrain

While all those things we do typically have the effect of eventually dulling the ache we feel in response to the death of a loved one, there are circumstances when those rituals and practices of mourning prove insufficient. In the stories I have encountered around street memorials in Kensington, I find they are seldom about people dying of old age or from a protracted illness. They are tragic, often violent stories, sometimes intimating injustices: someone shot on a corner; someone stabbed in a fight over a girl; someone violently assaulted and murdered; a hit-and-run; someone dying from a drug overdose; a very young person dying suddenly from an undiagnosed condition.

These are typically the circumstances under which memorials appear on the streets and sidewalks or on the walls of buildings. And this takes me back to the idea of the refrain: keeping the forces of chaos that threaten to undo us at bay through acts of repetition. Death under any circumstances feels like chaos. It is certainly an undoing–or connections and relationships, of time–that threatens us. But under tragic and unjust circumstances, I think it must be more so. Like September 11, some deaths simply require more than our typical rituals and habits of mourning can accomplish on their own.

The memorials for Frannie Girl seem to function in a similar way. At this point, the circumstances of Frannie’s death are unknown to me (though I am actively seeking information about her). But I think we can learn something about vernacular memorials from this example. Consider the locations. The wall of a block of small garages used by people in the neighborhood for projects and storage. The exposed wall of a row home that looks onto a vacant lot used for parking. The wall of a poppi store that went under during the pandemic. A wall behind Kensington High School on which students painted a mural and which has been tagged. Publicly visible, relatively uncluttered by graffiti, and unattended, these spaces which were once found throughout the neighborhood have recently become more rare.

RIP Frannie also clues us in on a vocabulary of memorial work. Symbols like the heart are quite common. Phrases like “R.I.P.” and “fly high” signal that this is indeed a memorial, not just a tag. The birth and death dates are also an important feature that frequently–though not always–appears in vernacular memorials. Memorials usually appear on the site of the remembered person’s death or perhaps the last place they were seen alive. This is probably not the case in this instance (though one of the four sties may be the spot). But that exception makes the “territorial” aspect of them more important.

They are repeated, perhaps, in the same way as one whistles a tune in a dark, forrboding space; repeated like the wall of sound we create with our ear buds, with the TV in our homes, or like the music from the PA at a block party. They are repeated to create a territory to hold back the forces of death and chaos. Perhaps for the writer and those who knew Frannie, they afford the ability to communicate grief (mourn) in a way that also allows them (and Frannie) to remain anonymous.

At this point, these are just speculations. But I think this recent addition to the neighborhoods’ collection of memorials created by ordinary people to express their losses may help to illuminate some of the other stories that memorials tell. And maybe, too, it can help all of us understand better how we experience and express our own losses.

Update: January 2024

After spotting some new activity on this memorial, I returned home and renewed my search for information about Frannie Girl. I came across an obituary for Frances “Frannie Girl” Jackson, born and raised in Kensington, who dates match those on the memorials. R.I.P. Frances. Love the many friends and family members she left behind.