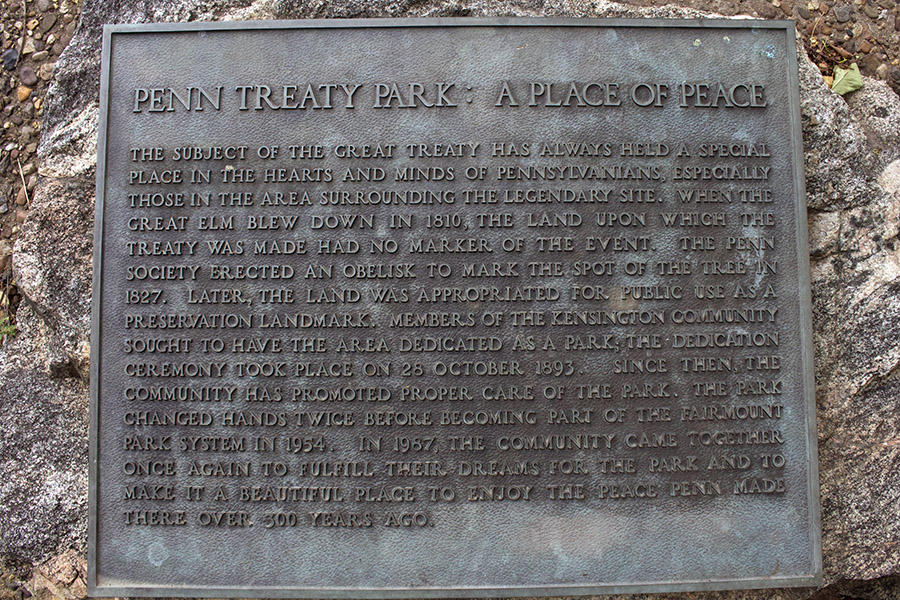

Not far from where I live in Kensington there is a little park sandwiched between a derelict-looking power plant and a monstrous casino complex on the shores of the Delaware river. It is called Penn Treaty Park And according to tradition, it was under an elm tree on that very site in 1682 that William Penn, founder of Pennsylvania, entered into a treaty with the Lenni Lenape tribe. Although Penn had been gifted the land by the British crown in lieu of a debt owed to Penn’s family, he made a treaty and received a belt of wampum—a symbolic and ritual exchange of esteem and value—from the Lenape. The elm tree under which all this is alleged to have occurred has been venerated for generations. According to legend, British General John Graves Simcoe posted guards around it to prevent its being used for firewood by colonists during the War of Independence. According to a plaque on the site the elm was destroyed in a storm in 1810, about 130 years after the signing of the treaty. But its “great, great grandchild” is venerated in the park by a tasteful, sturdy metal fence and a bronze plaque of its own.

This is a story about a place. It cannot be proven or disproven. There is no way to verify the identity of the elm and its relationship to The Treaty Elm. The same goes for the stories about the supposed destruction of the treaty document by Penn’s avaricious sons and the veracity of the claim that a wampum belt donated by Penn’s great grandson to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania was one his ancestor received on that day. These stories are, however, firmly entrenched in our collective memory as stories—or better, as a story of stories, a myth. Even the site itself is a story, or rather a place made out of stories.

According to tradition (and Wikipedia), this place was called “Sakimauchheen Ing” by the Lenape. The name has been europeanized as Shackamaxon and preserved even now in that form as the name of a nearby street and a creek in the area. This term suggests it was either a summer fishing village, a special place where new leaders were inaugurated and feted, or perhaps even both. Even this alternative story about the place, which at least acknowledges an indigenous point of view, is just that—a story. It may well be that “we” needed it to be a sacred place for king-making for the aboriginal people we dispossessed in order to legitimate our own local and national narratives.

My point is not that Penn Treaty Park is to some extent based on fictions (it certainly is), or even that these stories privilege and service certain interests at the expense of others (they undoubtedly do). It is rather that this park exists where it is, when it is, in the way it is, as an embodiment of these stories. Penn Treaty Park is a monument to those stories and of the stories we have told and continue to tell about it. It is also a monument to the events we imagine happened there. The monument’s content is not the past in itself but a myth about the past. It is an excellent, local example of a particular, common form of collective memory, termed “official” or “monumental” memory. In what follows, I want to consider what makes Penn Treaty a site of “official” memory. In doing so, I want to invite you to consider what makes it different from the various examples of vernacular memory documented on this website.

official memory is monumental

Official memory is “monumental” in every sense. To explain, it might be easiest to begin with that word, “monument.” It is composed of a verb (Latin, “to remember”) which suggests an action, and an ending that nominalizes that action by turning it into a thing. Similar to the word “movement”—which turns the verb, “to move,” into a thing, “a movement”—the word “monument” turns remembering into a thing. Importantly, the Latin root from which the word comes (monere) was not simply meant to suggest the act of recalling the past or remembering where you parked your chariot. It carried with it other meanings: to “’admonish,’ ‘warn,’ ‘advise,’ ‘instruct.’” Monuments, then, do not just sit quietly, suggesting that you recall the past. Monuments command, advise, instruct us to remember. The next time you walk past a monument, regardless of what it’s content may be, just imagine that it is ordering you– “Remember!”–with a stern wag of its finger. You will have the right sense of the word ‘monument.’

Consider Penn Treaty. As you enter the park, you cannot help but encounter the statue of William Penn. To encounter it in person is to measure its grand scale against that of your own, ordinary body. His larger-then-life likeness is both physically separated from you by a dais of stone, concrete, and metal bejeweled by large, bronze plaques. It is also elevated several feet above you by the dais and a large, polished granite pedestal. Much as the ancient kings of past civilizations would parade both supplicants and emissaries past large likenesses of themselves to remind them of the King’s divinity, so too are we confronted by the grandeur of the official memorial and the memory of William Penn and the Great Treaty.

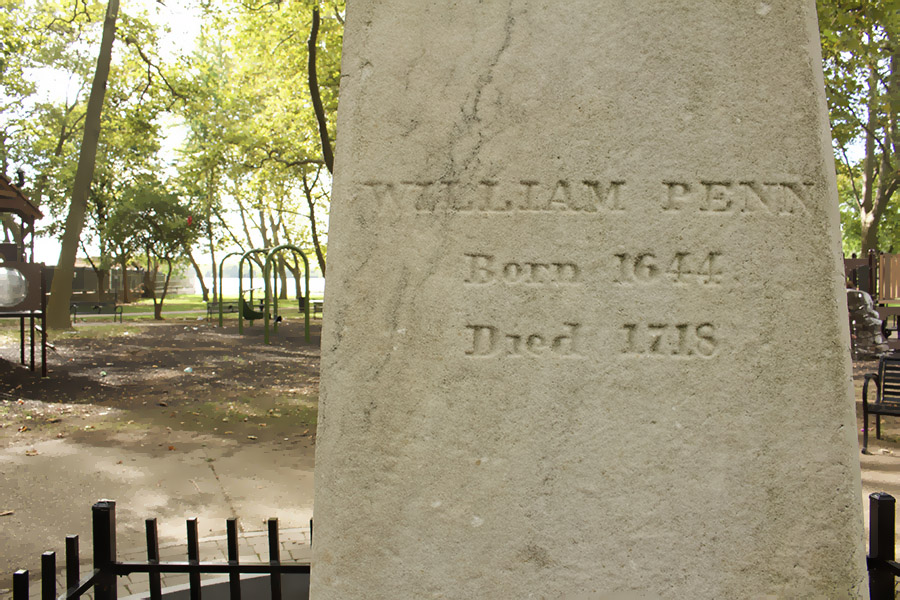

As you walk the paved pathways that wind through the park and around the casino, you are compelled to process past a number of lesser monuments: the Penn Society Obelisk, the descendent of “The Great Elm” under which the treaty with the Lenape was made, a small memorial to a Fishtown resident, William “Bill-Bill” Schneider, who according to his obituary went to the park throughout his life. (Wait, is that a piece of local, vernacular memory in there? Good question!) These others do not—cannot—compete with Penn’s memorial status. They bask in it, resonate with it, echo it.

official memory is sacred

The presence of other memorials suggests this is sacred ground. Not unlike the way a graveyard constitutes sacred ground. In fact, the whole 7 acres of the park has been “sanctified,” set aside from the hustle and bustle and business of the rest of the City’s public space. This space is dedicated to communicating to everyone the command to remember Penn and his treaty.

The “thingness” of monuments even on their surface suggests another defining feature of official memory: its material form. Unlike the painted and graffitied walls, the flowers and candles, improvised shrines and other examples of vernacular memory which you can find on this website, Penn Treaty is cast from bronze, hewed from marble and granite, tied into the very earth of the city. Graffiti gets painted over. Flowers wither. Candles burn out. But metal and stone endure longer than generations. Memorials like Penn’s statue are what the Canadian historian Harold Innis termed “time-biased” media. Like the great Sphynx and the pyramids of ancient Egypt or the columns of the Parthenon, they are not very portable, but they are certainly made to last.

Monuments “emphasize time and continuity,” Innis wrote, and therefore preserve what is traditional and “sacred” of the past (33). As with our diminutive size in relation to Penn’s, so our experience of time is diminutive, fleeting, and temporary when compared to the granite form and mythic content of William Penn’s monumental temporality. As Donahoe suggests to encounter a monument is to encounter time as a durable, consistent and coherent thing. He speculates that monuments represent “our desire to produce something that outlives us, something that contributes to a cultural world that will continue”(264-265). We need to believe that in some way some part of us and our way of life endures beyond death, and monuments afford us the “substance” of that hope and the “evidence” of a future we will not see.

official memory is specialist

Official memory tends also to be a specialist practice. Not just anyone can cast bronze, carve a granite block, or create a marble obelisk. Not just anyone can engrave words on these hard, enduring surfaces. Nor can just anyone produce and display a large statue of themselves in a prominent, public place. A number of artisans and other specialists must be employed not only to conceive and create, but also to curate and maintain official memory. And this is not just a one-time deal. It must be ongoing. Consider how much Egyptian and other ancient monuments were degraded and how many were lost because no one was left who knew them, knew what they meant or cared enough to expend the resources needed to keep them from being buried by time. On the day that I went to take the photographs on this page a crew of several workers was busy ruining a perfectly blissful, quiet morning with the sounds of weed-whacking, hedge-trimming, leaf-blowing and lawn-mowing.

Here we can make a useful contrast between the vernacular and official forms of collective memory. Many vernacular memorials are constructed of less durable stuff by non-artisans. While a very few show evidence of maintenance or care over time, they are the exception and not the rule. Philadelphia’s Mural Arts Program offers a borderline case. The organization is an elite (not “elitist”–there is an important difference!) arts and culture institution. Its website claims it is “the nation’s largest public art program.” It was originally a City office created to combat the burgeoning “crisis” of graffiti facing the City in the late 1970s and early 1980s. But it has since become a non-profit organization that not only contributes to the City’s official memory in a way that respects the diversity of stories and voices of the City’s residents, it also educates youth. The murals they produce involve the direction and oversight of artists, but they also involve the contributions of youth and incarcerated people who participate in the murals’ making. The Mural Arts program, however, is an institutional and institutionally supported form of official memory, one that is specializes in the production of public memory.

official memory is elite

Official memory thus exists by virtue of elite institutions. Not many people can afford to have a bronze or marble statue of themselves made, let alone have the power to have it put on display in public in perpetuity. Monuments exist at all because of philanthropic institutions, historical societies, local, state, and federal institutions, politicians, educational institutions, and of course the economic institutions which produce the wealth that increasingly holds sway over public life. And all of these are controlled by elites.

These institutions exist to serve and preserve their interests. And official memory also serves and preserves those same interests. William Penn and the many foundations, societies, institutions, and organizations which bear his name are connected to Penn Treaty park, even if they are not directly responsible for its existence and maintenance. They resonate with it and with one another and have the status they do in large part because of it. The park is the material, public, enduring embodiment of the stories on which all of these institutions depend: much as the various memorials in the park resonate with Penn’s monument and participate in its “sacredness,” so to the various elite interests which sustain the park’s continued existence.

The link between political and economic interests and public memory may be more obvious when we look at the monuments to confederate generals and politicians which began appearing throughout the South during the 1890s-1900s. In that case, the public message was—as the signs above the restrooms and water fountains pointed out to everyone—for “whites only.” There is nothing so aggressively and obviously racist on display in Penn Treaty Park. But as a site of official memory, it is no less redolent with power. Considered from the point of view of the present, it is a testament to the power to dispossess the original inhabitants of the land.

It is also a testament to the power of the myth, that Penn and the Lenape swore to be best friends forever, and thus the Lenape freely and willingly gave away all rights to their land in perpetuity. As I said at the beginning, according to the Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia there are no primary sources, official documents or records of the event having occurred. Even if it did occur, it certainly wasn’t as we have come to imagine it–a document being signed, wampum exchanging hands, all peace and love. That is the result of much literature and painting. And even if it was all peace and love , there is no official record of the location of the supposed meeting. The site of the present-day park was not declared to be the location of the treaty until 1827–almost 150 years after the fact. That is when the Penn Society stuck its obelisk in the ground and declared it so. “To build a monument,” writes Marcel LeClère, “is first and foremost to compose the city about it”(688).

Conclusion

To sum up, official memory is “monumental,” time-biased and sacred, specialist and elite. Whatever the content of the memory being monumentalized, official memorials are above all public displays of the power to compel others to remember. While such official memorials may be modified, neglected, ignored, even lost and forgotten in time, they exist at all, are sustained, and remain for however long they do as an expression of social, political, and cultural power. There is much that vernacular memorials share with official, monumental memorials. They are both public. They both involve the memory of groups. Both are material expressions of culture. And, perhaps more important, they both depend on a cultural “sense” for remembering. That is, the fact that we “just know” when we encounter them that memory is happening in and through them suggests a shared, memorial sensibility.

However, I want to conclude by inviting you to reflect on how vernacular memorials, like those found in the map and gallery pages of this site, differ from the kinds of official, monumental memorials that can be found throughout the neighborhood of Kensington, the city of Philadelphia, and indeed in communities throughout the nation and the world. I also want to invite you to think about the “memorial sensibility” that they reflect. Then take a look around you, wherever you might be, and see how your community remembers. You might be surprised at what you find there.

Drop me a note in the comment box or hit the contact button to let me know about what you find.

sources

Donahue, J. “The Betweeness of Monuments.” Interpreting Nature: The Emerging Field of Environmental Hermeneutics. (Clingerman, et al, Eds.). New York: Fordham Univ. Press. 2004.

Innis, H. The Bias of Communication. Univ. of Toronto Press. 1999.

LeClère, M. Paris. Saint-Jean-d’Angély: Bourdessoules. 1985.

Newman, A.. “Treaty of Shackamazon.” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Accessed: Sept. 19, 2020.

Good job well written and a little light into how we as a society hold on to our history

Thank you for reading – and for the kind words!

You have done a amazing job with you website

This is a great inspiring article.I am pretty much pleased with your good work.You put really very helpful information…

Wonderful illustrated information. I thank you about that. No doubt it will be very useful for my future projects. Would like to see some other posts on the same subject!